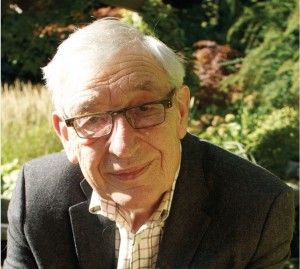

Richard Simeon Obituary

December 9, 2013

Late Professor Richard Simeon defined political discourse in Canada

by: Michael Valpy

Richard Simeon was one of the great scholars of Canadian federalism and constitution building of the past half-century who did much to define the political conversation in his country in an era now largely vanished behind history’s veil.

As a teacher and mentor, he was idolized by his students and credited with influencing a whole generation of young Canadian political scientists – both Quebeckers and anglophones – who labelled themselves “Simeon’s people.”

His advice on federalism and decentralized governance was sought internationally. He played a major role in helping post-apartheid South Africa shape its institutions of public administration. He received some of the highest honours his profession could bestow, and he was universally respected in provincial capitals as diverse as Edmonton, Toronto and Quebec City, although, because of his beliefs, he was somewhat less appealing to Ottawa.

Dr. Simeon died of cancer in Toronto on Oct. 11 at the age of 70.

He personified, iconically, so much of the debate that gripped Canada in the steamy two decades of constitutional strife that closed out the 20th century, and in many ways, the discourse in which he was so deeply involved has, like his life, ended.

Federalism is no longer high on the agendas of Canada’s governments. The two solitudes of French and English Canada are virtually complete, the disengagement all but absolute. Quebec is not particularly important to the national government, possibly for the first time in Canadian history.

“Stephen Harper’s view of Canada is not one of bringing together people of different views – and that’s a very powerful change,” said University of Ottawa professor Martin Papillon, one of “Simeon’s people” whose doctoral dissertation he supervised.

Dr. Simeon was the definitive bridge-builder between the political science communities of Quebec and anglophone Canada in the 1980s and 1990s, devoting himself to keeping the two sides talking about the country’s constitutional future after spectacular and heated political failures to redefine Quebec’s presence within the federation.

His view of federalism was in harmony with his view of Canada, Dr. Papillon said – not as a structure of principles, but as a structure of compromise, something never quite achieved or finished, always a work in progress.

He was decidedly not a Pierre Trudeau centralist, and thought the former prime minister had got the country wrong.

In the constitutional struggles, Dr. Simeon played a crucial role in keeping the lines of communication open among politicians, public servants and academics – first as director of Queen’s University’s prestigious Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, from 1976 to 1983, and then as head of the university’s School of Public Administration from 1985 to 1991.

He joined the University of Toronto as professor of political science and law in 1991. Dr. Simeon was a constitutional adviser to Ontario premiers William Davis, David Peterson and Bob Rae.

His engagement with South Africa began with a phone call from former top Ottawa civil servant Al Johnson, who had been appointed senior adviser to the South Africa/Canada Program on Governance in 1992 in the midst of South Africa’s transition to a multiracial democracy led by Nelson Mandela.

“Richard,” Mr. Johnson said, “they are having provinces in the new South Africa, so we had better tell them how provinces work.”

What followed was a lengthy collaboration between Dr. Simeon and University of Cape Town legal scholar Christina Murray, teaching and writing about comparative federalism and constitutionalism in South Africa in its difficult evolution to multilevel government.

The new constitution reflected much of their thought on institutional arrangements and intergovernmental relations.

Dr. Simeon’s work has been quoted by the Constitutional Court of South Africa. Perhaps more importantly, in the first years of South Africa’s democracy, it influenced understanding of how the country’s new institutions were intended to operate.

“He always tied arguments about how institutions work to larger principles – deepening democracy, developing strong government institutions, respect for all persons,” Prof. Murray said.

“I was impressed by his commitment to seeing things work. He had a kind of realistic optimism that gave courage to me and others to persist even when the prospects of getting people to think about creative ways of making institutions work seemed pretty bleak.”

His determination to seek compromise and span the gulfs between conflicting groups was what his University of Toronto friend and fellow political science colleague, David Cameron, described as a primal instinct.

Dr. Simeon’s time at Queen’s, as an example, coincided with a strong neo-Marxist period in the social sciences, an ideological bent he did not share but was eager to explore in search of common ground. A colleague dismissed his efforts as the work of “just a bourgeois bridge-builder” – which delighted Dr. Simeon, who put up a sign on his office door reading, “I’m just a bourgeois bridge-builder.”

Said Dr. Cameron: “He joked about himself as professor-on-the-one-hand and professor-on-the-other-hand – always that effort to find balance and accommodation. It made him a very appealing, receptive, open person for all kinds of people and their views. Francophone doctoral students who came to [the] University of Toronto felt he understood them.”

Sir Richard Edmund Barrington Simeon, 8th Baronet of Grazely, was born in Bath, England, the descendant of 200 years of hereditary baronets who were members of Parliament, public servants and landowners. After changes to inheritance taxes impoverished the family, his parents, Sir John and Lady Anne Simeon, along with eight-year-old Richard and his two sisters, immigrated to British Columbia, where his father, knowledgeable about estate management, became a park ranger.

Dr. Simeon – he never used his title, which he inherited on his father’s death in 1999 – attended Vancouver’s St. George’s School and University of British Columbia, graduating with a bachelor’s degree.

He worked on the student newspaper, The Ubyssey, and had part-time and summer jobs as a reporter at the Vancouver Province. He was offered a full-time position at the Ottawa Citizen but decided in favour of academia.

He went to Yale University on a Woodrow Wilson scholarship and earned his doctorate with an award-winning dissertation, Federal-Provincial Diplomacy, that brought a new theoretical approach to federalism in Canada.

He used the framework of international relations – how sovereign states deal with one other – to analyze how Canada’s federal and provincial governments should relate, and found it produced good results.

His 1968 dissertation – described by the prize jury as “a classic whose influence stretches far beyond Canada’s borders” – became his most influential book. It was reissued five years ago, an almost unheard-of achievement for a doctoral thesis.

It made his reputation immediately and was the beginning of a steady stream of publications on federalism and other topics of Canadian and international governance, some 20 books and 100 articles and book chapters.

His last writing appeared as the closing chapter of a Festschrift honouring his scholarship that was published last week – he told of what got him interested in federalism. Detailed notes for an article he was unable to complete will appear next spring in the publication of Queen’s Institute of Intergovernmental Relations’ annual State of the Federation conference.

Keith Banting, who was associate director of the institute when Dr. Simeon was director, said his colleague was known for his intellectual breadth. “He could always see in any situation very different perspectives, and he was constantly trying to build bridges across those different perspectives. So the bridge-builder thing was important intellectually as well as politically.”

Dr. Simeon said of his own work: “My view was not so much to take sides or go to war for national unity, but rather to help promote mutual recognition and understanding across the linguistic divide. This search for compromise, consensus, and accommodation, more than any partisan position, was and is my core belief and has shaped my responses not only to many aspects of Canada’s linguistic, regional, and aboriginal differences, but also to many international cases as well.” He was, in fact, deeply suspicious of anything that struck him as a threat to consensus.

Thus he turned down an invitation to be head of research for Pierre Trudeau’s 1977 Task Force on Canadian Unity, better known as the Pépin-Robarts Commission, after its two co-chairs, Jean-Luc Pépin and John Robarts, because he thought it would be too much a vehicle for Mr. Trudeau’s views and therefore intellectually questionable.

What the 1982 patriation of the Constitution meant for most Canadians was the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. What it meant for Dr. Simeon was a constitutional accord without the participation of Quebec, which deeply disappointed him and turned him into an activist for the Meech Lake (1987) and Charlottetown (1992) constitutional accords, both of which failed.

As the issues slid off the agenda of Canadian politics, Dr. Simeon increasingly turned to comparative federalism – looking at systems outside of Canada – and the quality of democracy.

“He would say occasionally that the unity of Canada is really important but it’s not the most important thing: Preservation of the high quality of democracy is very important,” said Keith Banting.

He danced, he canoed, he hiked, but nothing absorbed him like scholarship, conversation and engagement with people, said his wife, MaryEtta Cheney, a human resources consultant whom he met when she took one of his courses at Queen’s and later followed to Toronto.

Harvard University twice invited him to serve as its Mackenzie King Fellow. In 2004, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. In 2010, the American Political Science Association honoured him for a lifetime of distinguished scholarship.

His lectures were meticulously prepared, written out in full, and he read from them. “You’re not supposed to do that,” Ms. Cheney said, “but he was mesmerizing.” When he was asked questions by students, he’d often reformulate them into brilliant queries that students wished they’d asked.

He was fluently bilingual but spoke with a rough, working-class French accent, the result of working summers as a student with construction crews in northern Quebec.

He was a gentle, kind man, unfailingly generous with academic authorship, insisting that his name appear in alphabetical order rather than as principal writer.

He had an intense curiosity. At bedtimes, his daughter Rachel recalled, “he was so easy to convince to read another chapter because he was as engrossed in the story as I was.”